You calculate CAC by dividing customer acquisition expenses by the number of acquired customers. So if you got ten new customers from $1,000 marketing and sales spend over a certain period, the formula would be: CAC = 1000/10 = $100.

It’s an important marketing metric that’s especially useful when you relate it to your customer lifetime value (also known as LTV or CLV). But as with most things in data analytics, there’s a few pitfalls you should be aware of.

In this article, you’ll learn:

CAC is an averaged metric. It doesn’t take into account how diverse in value your customer segments are. That’s important to keep in mind because you should be willing to spend more to acquire the most valuable customers.

That said, there are two ways to use customer acquisition cost properly.

1. Use CAC in relation to LTV

CAC is an excellent marketing performance indicator when you measure it together with LTV. That’s because LTV is yet another averaged “money metric.”

The industry consensus on an ideal LTV:CAC ratio for SaaS businesses seems to be between 3:1 and 4:1. So if your LTV is $350 and your CAC is $100, you’re right in the middle of those ratios.

But because business models differ, you should try to run the numbers yourself to see how your other business costs and margins fit into such a ratio. The 3:1 to 4:1 range seems rather arbitrary as I didn’t find any data or case studies to back this up.

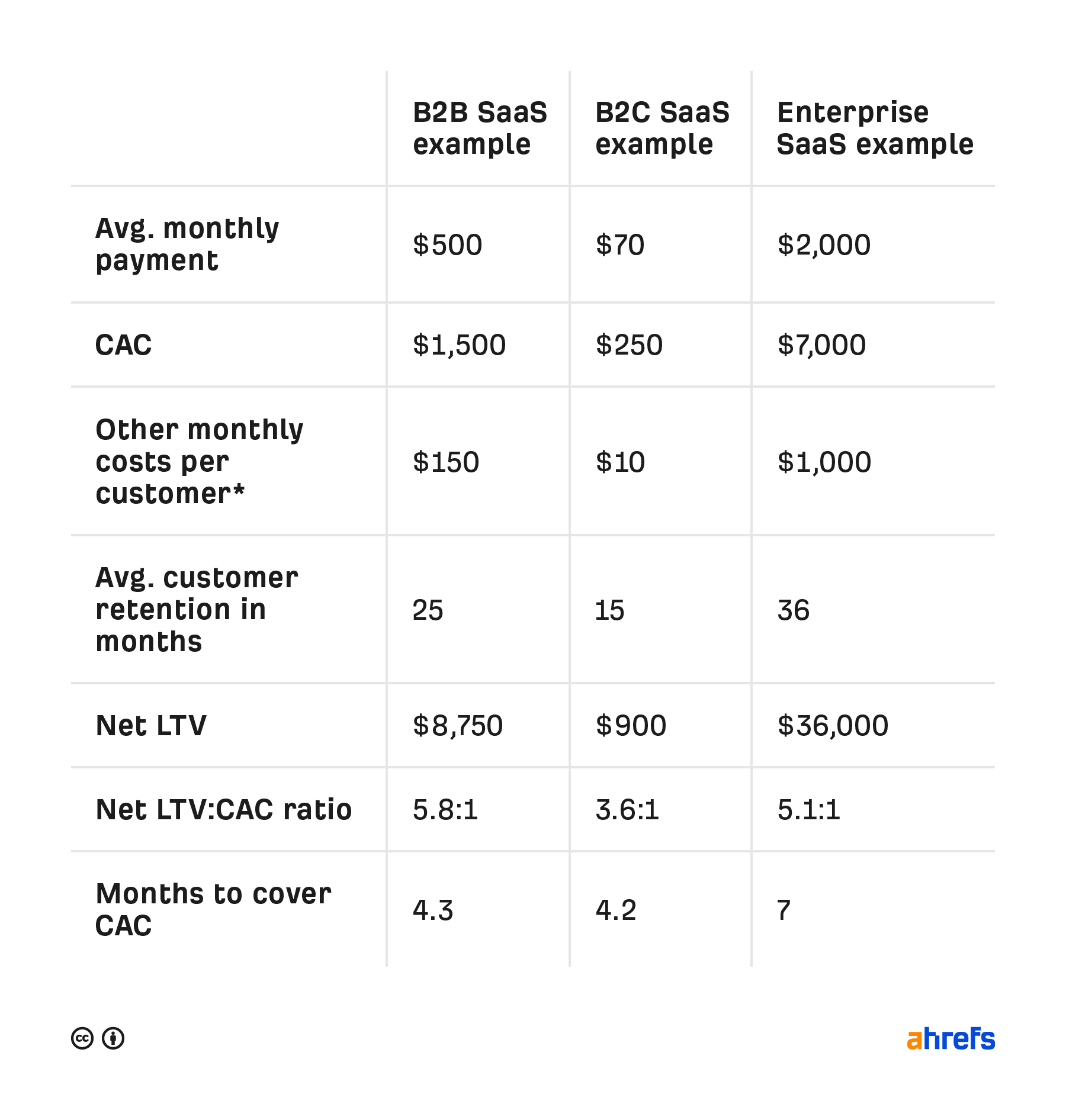

So, to illustrate how business costs might affect things, I created a few hypothetical scenarios:

Judging by the numbers alone, all of these business models seem to make sense even though the LTV:CAC ratios fall outside of the 3:1 to 4:1 benchmark for two of them. However, regardless of these numbers, we need to dive into marketing spend effectiveness to make any rational decisions based on CAC.

Why? Because reducing your CAC and being more effective in marketing don’t necessarily go hand-in-hand.

If CAC is too low, you’re limiting your exposure and under-spending on your marketing activities. That might look good on a paper in the short-term, but you’d be missing out on substantial growth opportunities in the long run.

CAC can also grow much faster in terms of percentage than your LTV while you remain more profitable. $10 CAC to $100 LTV is technically worse than $70 CAC to $170 LTV. The difference to cover your other costs and margins is $90 compared to $100 in the second scenario.

In conclusion, lowering your CAC shouldn’t always be your objective. You need to take your LTV, customer base growth, and overall marketing effectiveness into account when you think about adjusting your CAC.

2. Use CAC in isolation for performance ads channels

As tempting as it may be, don’t try to segment your CAC per all your marketing channels. It only works for your performance channels like PPC.

There are two reasons for this. I already talked about the first one, so here’s the second one:

CAC locks you in for short-term decision-making if you link it to separate marketing channels. For example, measuring CAC for display campaigns doesn’t make sense. That’s because these ads typically appear early in the customer journey when most people seeing it aren’t ready to buy your product or aren’t even aware of it.

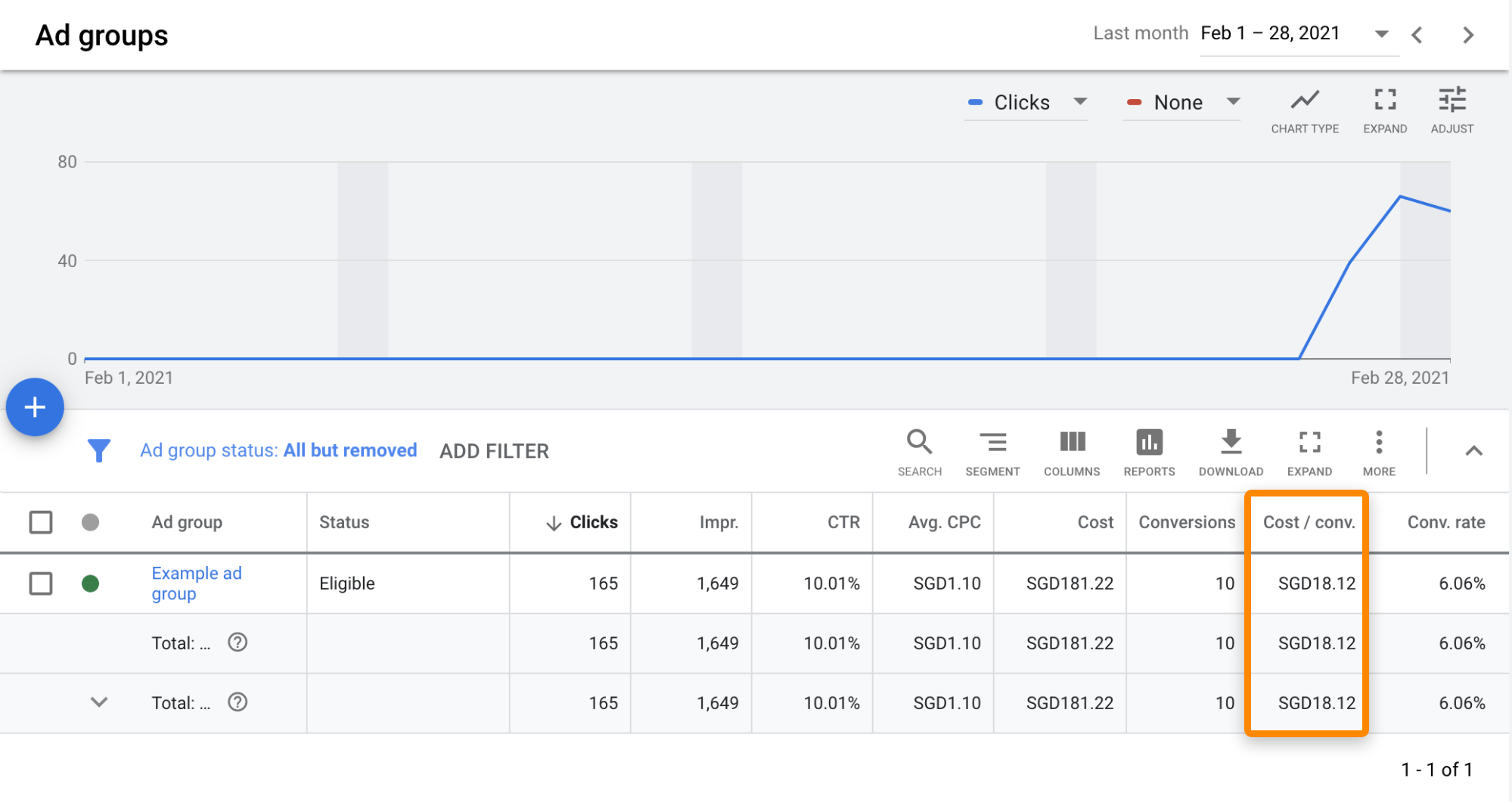

On the other hand, when it comes to the performance channels, Google Ads even has a CAC equivalent built-in. It’s called Cost Per Conversion:

We can take this channel-specific cost per conversion and use it to optimize the performance of that channel.

But you might be thinking that it doesn’t reflect CAC in its entirety. True, it only covers the cost of the last step in the customer journey. But that’s the best we can do here as you can’t attribute other channels’ costs to this.

Attribution is assigning credit to marketing channels that contributed to the conversion. Imagine a soccer player scoring a goal after getting a pass from three other players and one more teammate cleared the way. All of them helped to score the goal. But most businesses can’t make it work like this in marketing.

Default Google Analytics reports work with a flawed “last-non direct click” attribution model. That’s like giving 100% credit to the player who scored the goal. This player could be an analogy of performance marketing channels as they often take the full credit. I’ll talk a bit more about attribution in the CAC problems section.

Bottom line: if you try to account for CAC per all of your channels, you’ll run into attribution problems, and you wouldn’t account for other more brand-focused channels.

I hope it’s becoming clear that you should always strive for the highest effectiveness, which doesn’t necessarily mean reducing your CAC. But there’s no doubt that you should balance your paid advertising with cheaper and often more sustainable marketing channels and tactics.

Here are a few ways to inherently reduce your CAC:

With SEO and content marketing

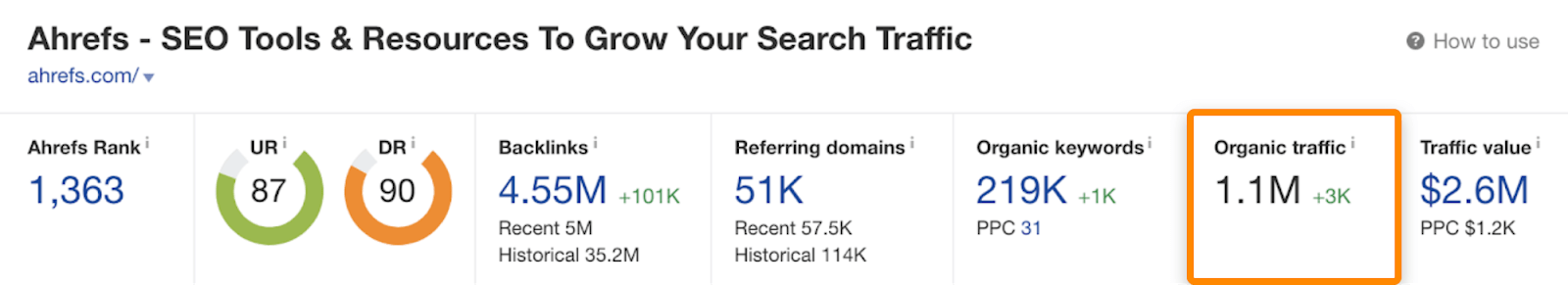

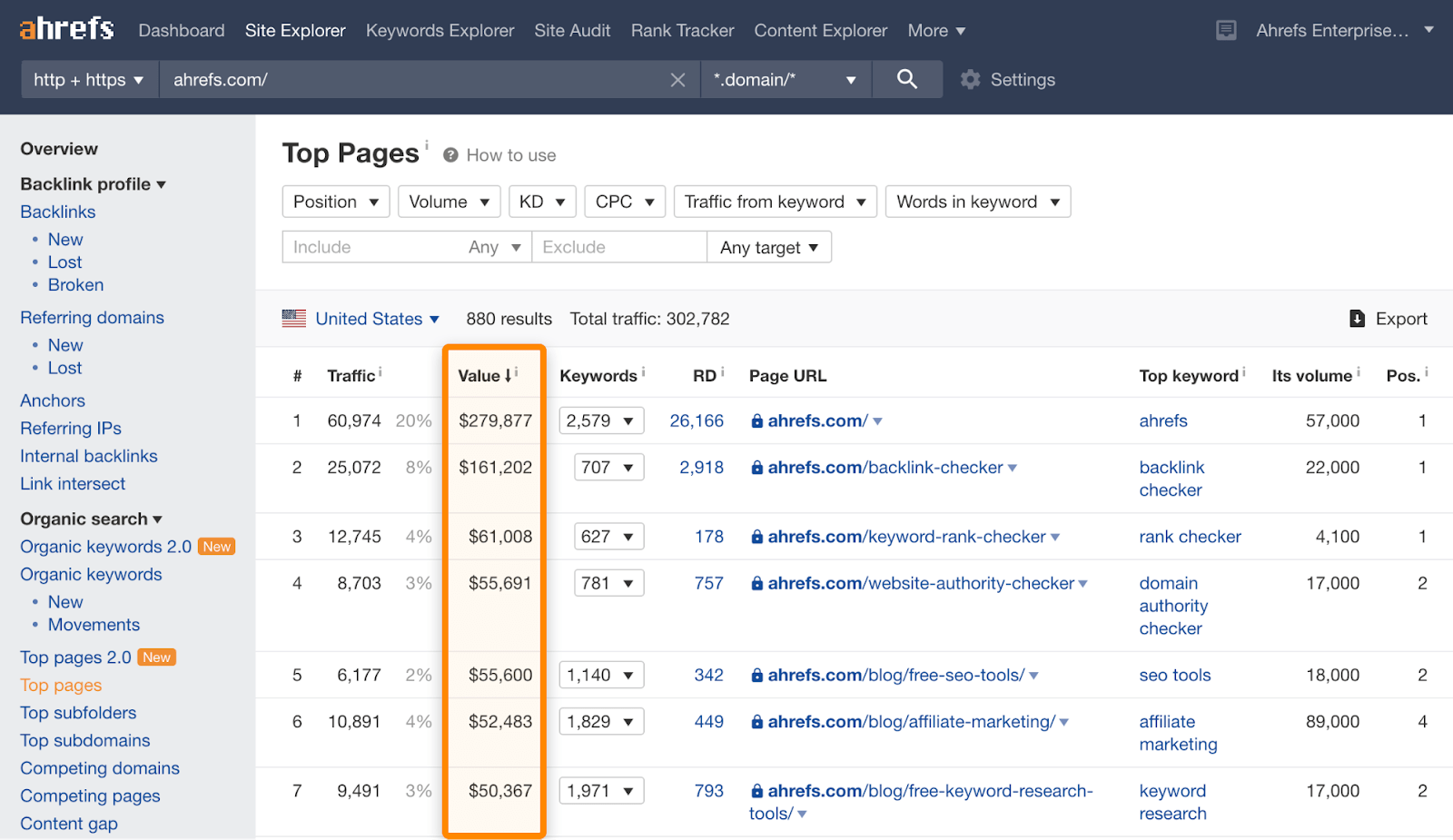

Organic search is the main traffic and conversion driver for many businesses, including ours:

The beauty of SEO is that it’s a suitable channel for all marketing funnel stages—from awareness to retention. People search on Google all the time.

So not only is SEO able to grow your business by itself, but it also massively helps your other channels—like paid search ads. That’s because you usually bid on keywords closer to the conversion stage, but a solid content marketing strategy includes content throughout the whole customer journey.

In other words, the combination of great SEO and PPC ensures that your brand is present throughout the whole customer journey. People would be less likely to convert if they heard about you only when they’re ready for the purchase.

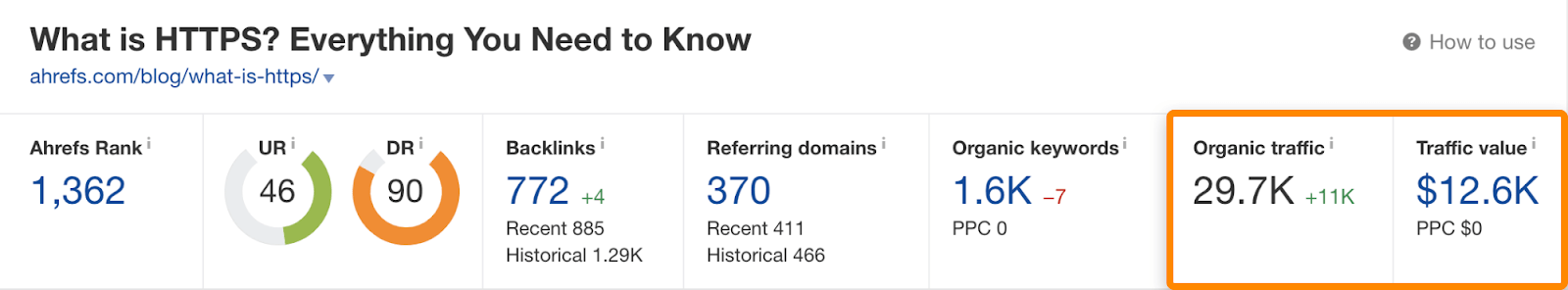

For example, our article “What is HTTPS? Everything You Need to Know” is not focused on a topic people usually search for when they’re ready to sign up for an SEO toolset. But it’s a relevant “top-of-the-funnel” content because some of the searchers have websites and might want to tackle SEO in the future.

Promoting such an article through search ads would be a questionable expense at best.

But thanks to SEO, this article gets almost 30 thousand clicks from organic search each month. That would cost us over $12,000 if we were to pay for the traffic in Google Ads:

And that doesn’t even take into account that you wouldn’t be able to get so many clicks from Google Ads anyway. That’s because most people skip the ads and click on organic search results only.

Of course, for keywords closer to the conversion stage, you often want your website to appear in both paid and organic search results. Ranking high in organic search results for competitive keywords can drive “free” traffic that could otherwise cost hundreds of thousands of dollars from Google Ads:

With Conversion Rate Optimization (CRO)

CRO is the process of adjusting your website or app to convert a higher percentage of visitors.

If you don’t optimize your website or app for conversions, it’s highly inefficient—even if it attracts tons of visitors. CRO is arguably one of the most efficient ways to make you more money and lower your acquisition costs.

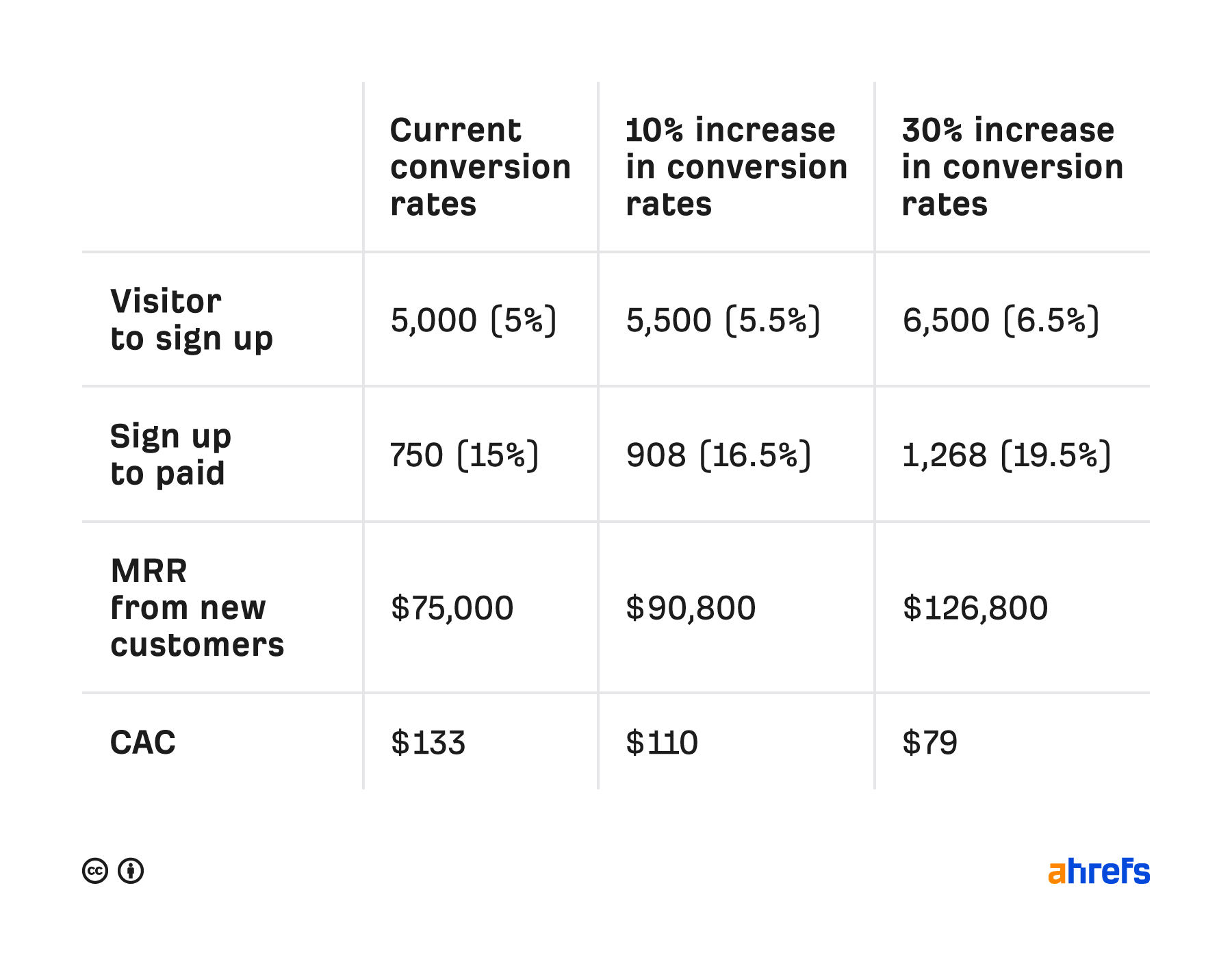

Let’s say that you drive 100,000 users to your website each month, 5% sign up for your free trial, from which 15% convert to your $100/month subscription. Your monthly marketing spend is $100,000.

Here’s how increasing your conversion rates influence revenue and CAC in this simplified case:

If you increase your conversion rates by 30%, your CAC drops by 41%, and your revenue increases by 69%. And you didn’t do anything to get more people to your website; you just worked with what you already had.

CRO is a whole marketing field that’s quite complex. You need to be versed in UX, copywriting, behavioral economics, user testing, analytics, and statistics.

You can try to learn CRO yourself as it’s useful across marketing. But investing in a CRO specialist is likely one of the quickest and most effective returns on marketing spend that you can do.

What you see in Google Analytics default reports under goal or e-commerce conversion rates is based on the number of sessions, not users. Take that into account when you look at user-level conversions like signups or payments. You can create a custom conversion rate metric based on users.

Create a solid balance between performance marketing and brand building

While you can’t really attribute brand-building activities to conversions, it plays a crucial role in converting visitors into customers. But that doesn’t happen overnight.

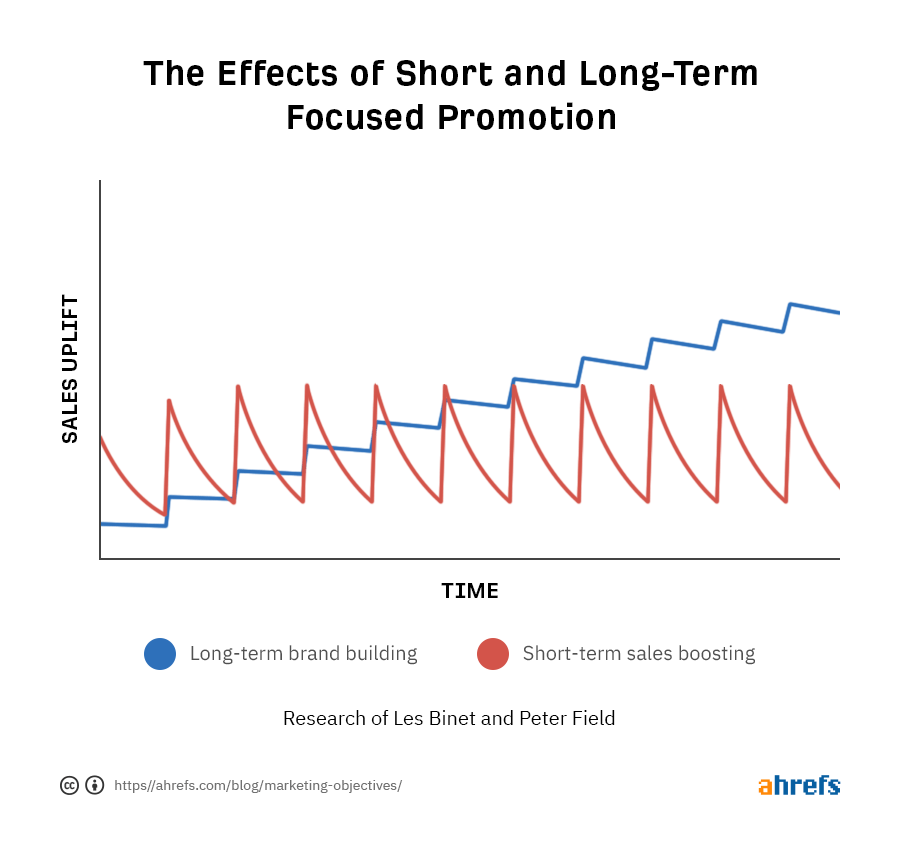

In fact, if you’re behind with brand building, it will actually increase your CAC in the short-term (~1 year) because these activities don’t have an immediate effect on your sales. But it will pay off very well in the long run, including a lower CAC.

As a general rule of thumb, the ideal balance between marketing spend on sales uplift and brand building is roughly 40:60. It’s one of the most important marketing concepts to keep in mind.

There’s a lot of research on this. The key takeaway is that brand building is proven to be the primary driver of long-term growth and success.

I already mentioned that CAC is an averaged metric with attribution problems. Let me expand on that before diving into two other more minor issues.

Attribution problems with getting more granular data

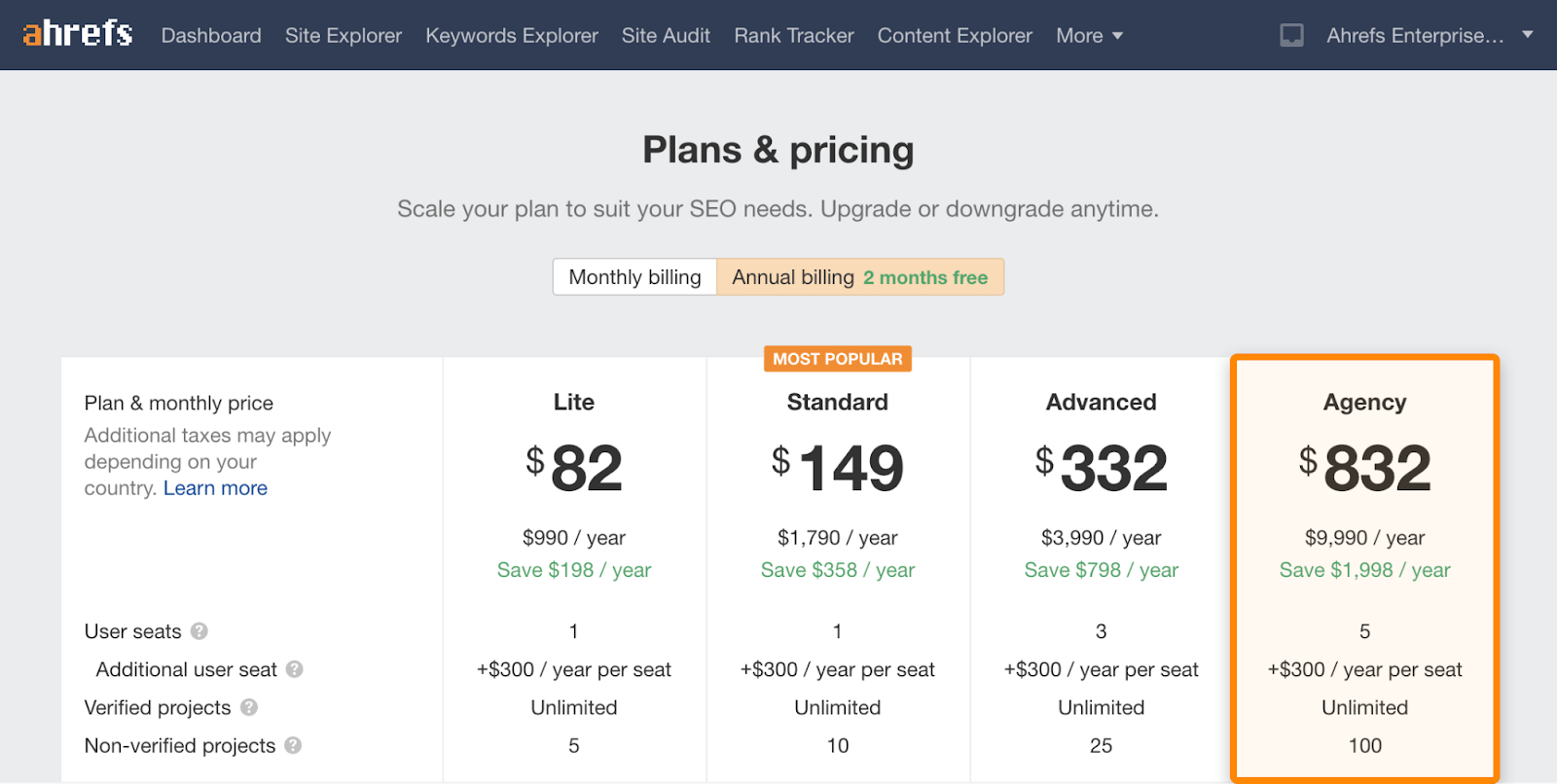

The most useful segmentation you could do with CAC would be with your customer segments. For example, if you look at our pricing model, we’re willing to spend many times more our average CAC on acquiring customers for the Agency plan:

But it’s close to impossible to get any reliable data to know that you spent $X on segment A or $Y on segment B, which would be needed for this calculation. Most of your marketing channels target multiple segments.

There are possible solutions for creating more reliable attribution models, but that usually requires tons of data and resources to create a custom data ecosystem. And even this can’t solve attribution problems some B2B businesses targeting enterprise segments face.

For that reason, I’d suggest most people stick to simple CAC formulas.

Taking your business cycle into account

It’s intuitive to take your monthly marketing and sales spend and divide that by the number of new customers you got that month. I used that too in the examples here. But this can only work if your spend is somehow constant month over month.

The problem lies in your business cycle. If you consider new users in March, then a significant portion of them converted thanks to your marketing activities in February or even earlier.

Of course, it’s impossible to track everything back, but you should know how many days on average it takes your visitors to convert from their first visit. If you have a 14-day trial, then the average business cycle will likely be between 2-4 weeks. Count with months for enterprise customers.

So, if you wanted to calculate the cost of customers acquired in March and your avg. business cycle is four weeks, you should use your February marketing spend in the formula instead.

It’s more useful for established companies

If barely anyone in your market knows about you, it won’t be easy to keep CAC within any reasonable range. Getting your first customers is a challenge.

For this reason, I’d recommend you start using CAC when you already have at least one marketing channel that consistently drives new customers.

Final thoughts

Like all marketing metrics, you shouldn’t get obsessed with CAC. It’s an important metric, but you should already know why it might not be the most suitable marketing KPI. Remember the pitfalls and all the other aspects of it when you analyze CAC.

Do you have any other CAC insights? Do you want to ask anything regarding this metric? Ping me on Twitter.