But can you go too far? Can you over-optimize?

Google says “yes”, in two ways.

Harmful over-optimization is, as Google’s Gary Ilyes puts it, “literally optimizing so much that eventually it starts hurting.” It’s possible to put so much effort into trying to rank that your pages cross into spam territory—and Google can reduce the rank of your content, or choose not to rank it all.

Google today is generally very good at identifying—and ignoring—many types of over-optimization. But there are a couple of tactics that still carry the risk of incurring manual penalties.

Keyword stuffing is the process of cramming a page full of keywords, in an attempt to rank higher for those keywords.

You’ll recognize keyword stuffing when you see it: keywords and their synonyms are repeated over and over, in sentences and paragraphs that don’t really make sense.

Finding the top mirrorless camera can be a daunting task. Yet, with our comprehensive best mirrorless camera guide, we simplify the process by ranking the best mirrorless camera models and the most reliable mirrorless camera brands.

It’s good practice to include keywords in relevant places, like titles or meta descriptions: you’re signaling to robots and humans alike that your page is focused on a particular topic.

But while keyword targeting helps pages appear in search results for relevant queries, keyword stuffing can have the opposite effect, turning helpful content into spam.

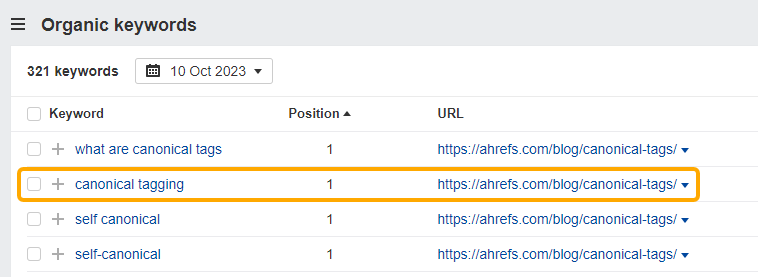

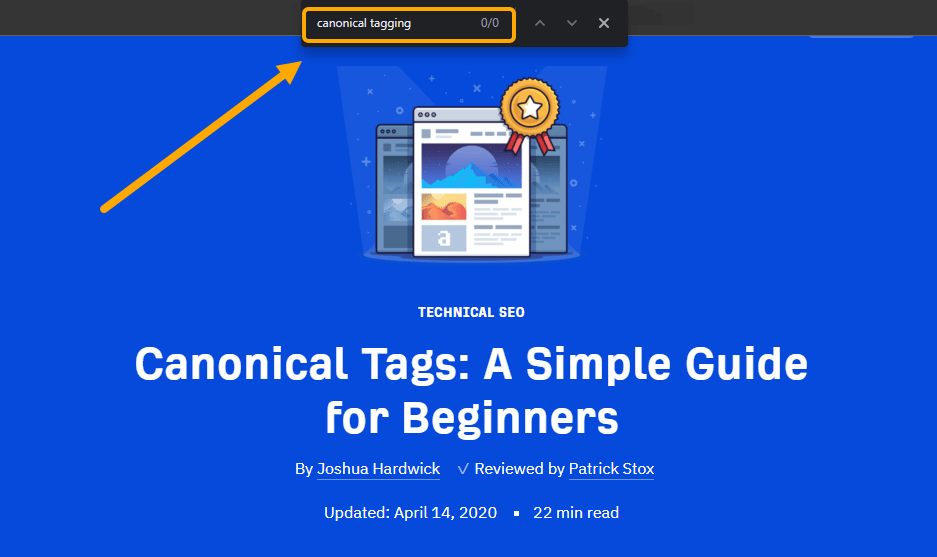

For Google, more keywords are not always better—and some pages even rank for keywords they don’t mention. Our blog post about canonical tags ranks #1 for the keyword “canonical tagging”:

Despite the fact that “canonical tagging” isn’t mentioned anywhere on the page:

You don’t need to cram keywords into every inch of your article. Write about your topic in useful detail, and create clear, relevant titles and headers, and you’ll mention plenty of keywords without any extra effort.

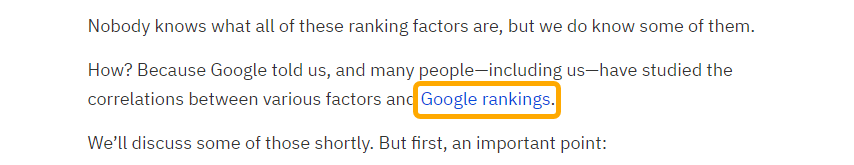

Anchor text refers to the clickable words in a link to your website. For example, this link has the anchor text “google rankings”:

When this anchor text matches the target keyword of the page it links to, it’s called exact match anchor text.

This can be helpful: Google looks at the anchor text of your backlinks to help understand what the page is about (and what it should rank for). But lots of backlinks with exact-match keyword anchors can be a clear sign to Google that links are being bought or influenced: something which is overtly against Google’s spam policies.

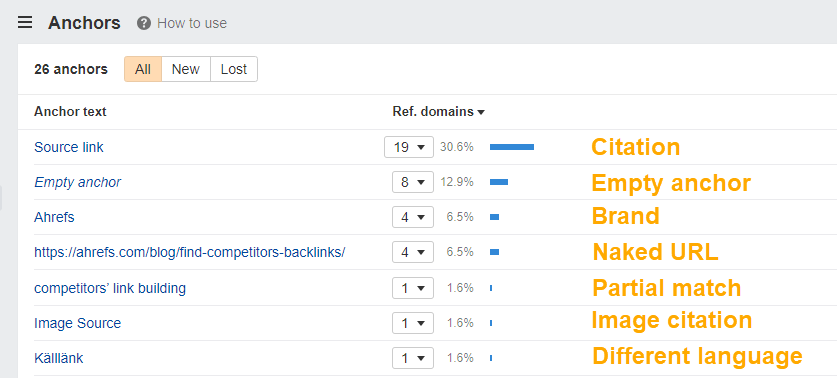

Natural backlink profiles contain a mixture of different types of anchor text: some exact match keywords, but usually many more partial match keywords, brand references, naked URLs, image links, and random words.

Here’s an example of a natural backlink profile:

Link-building is a core part of SEO, but it’s not helpful to obsess over the anchor text of every URL. Focus your energy on getting links in the first place, and leave the anchor text to the person linking to your site.

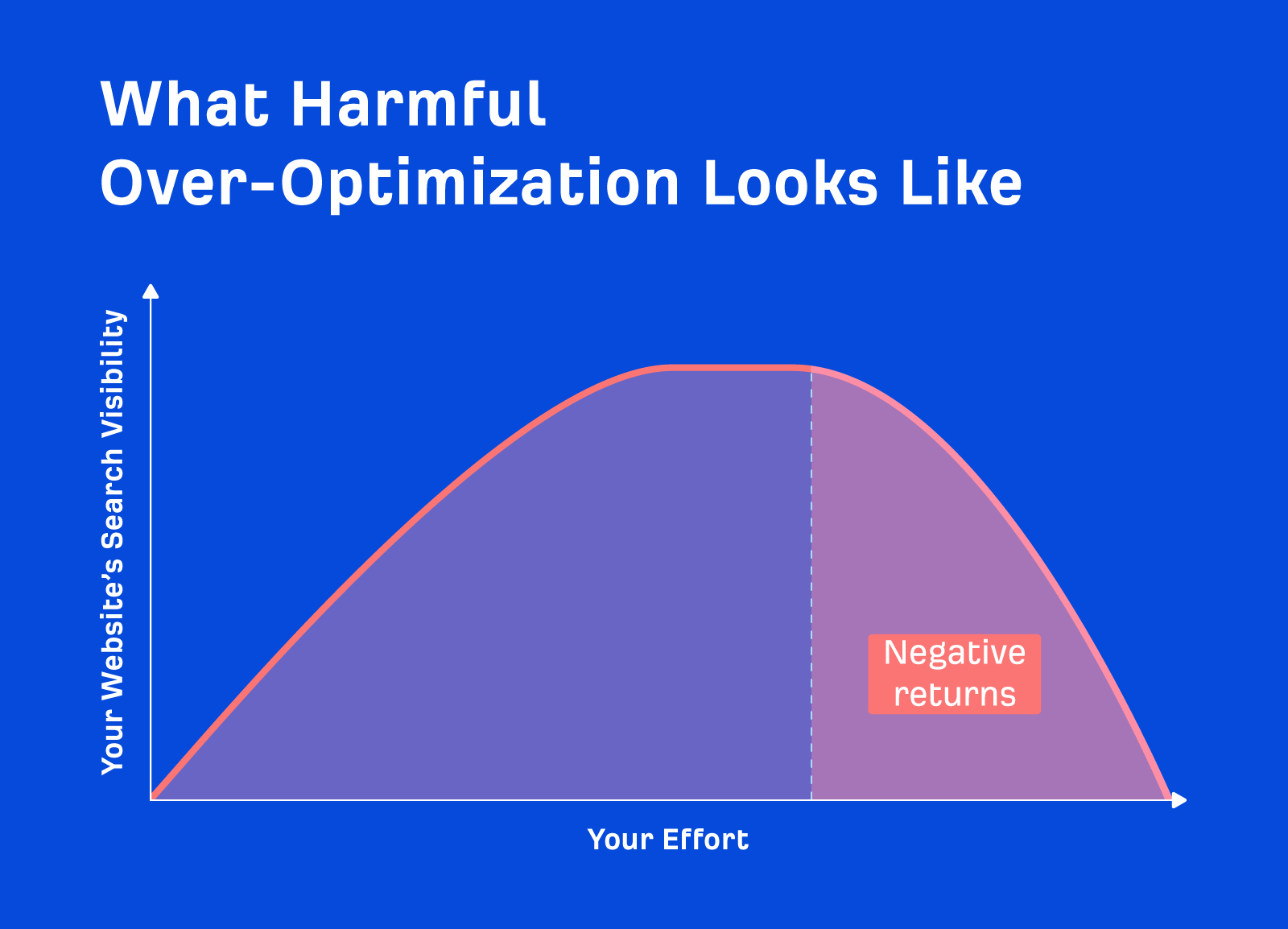

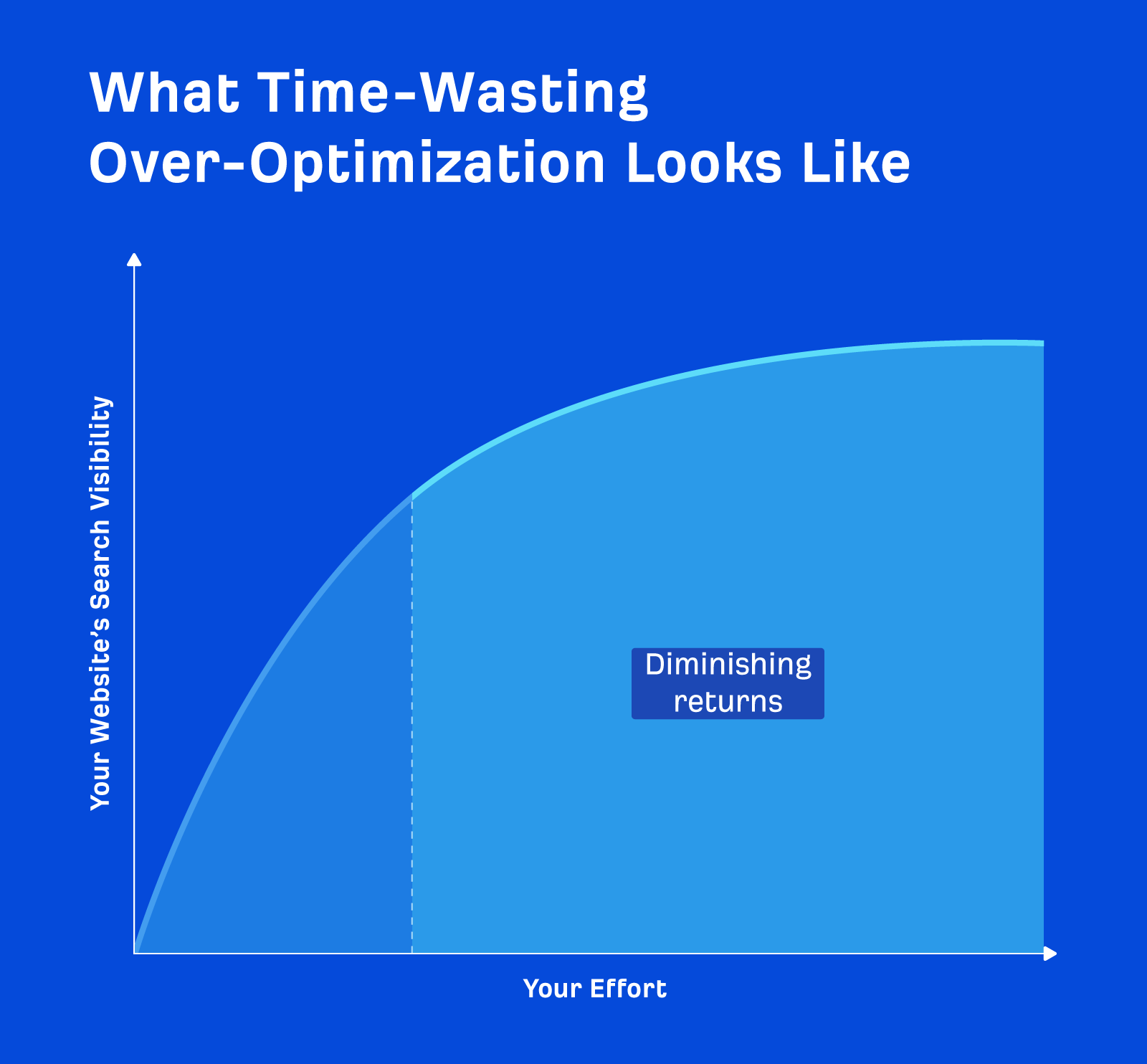

Other types of optimization suffer from a different problem: diminishing returns. Past a certain point, your continued effort has a smaller and smaller impact on search visibility. As Google’s John Mueller puts it, “focusing on all of the small details that make tiny tiny tiny differences.”

Here are a few examples.

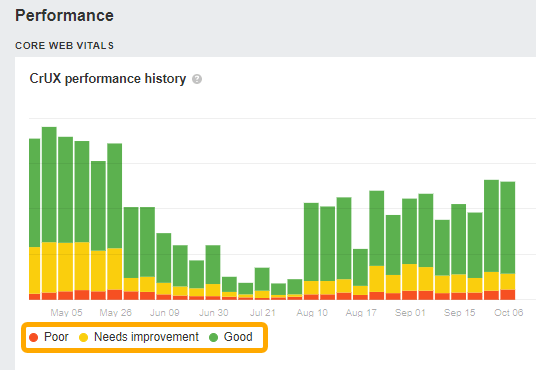

Core Web Vitals are metrics used to measure the speed and user experience of a website page, and they form part of Google’s calculations for ranking pages.

Core Web Vitals measure the performance of your page across three different tests. The page’s performance is scored as either Poor, Needs Improvement, or Good. For pages that have data available, you can see these scores in Site Audit’s Performance report:

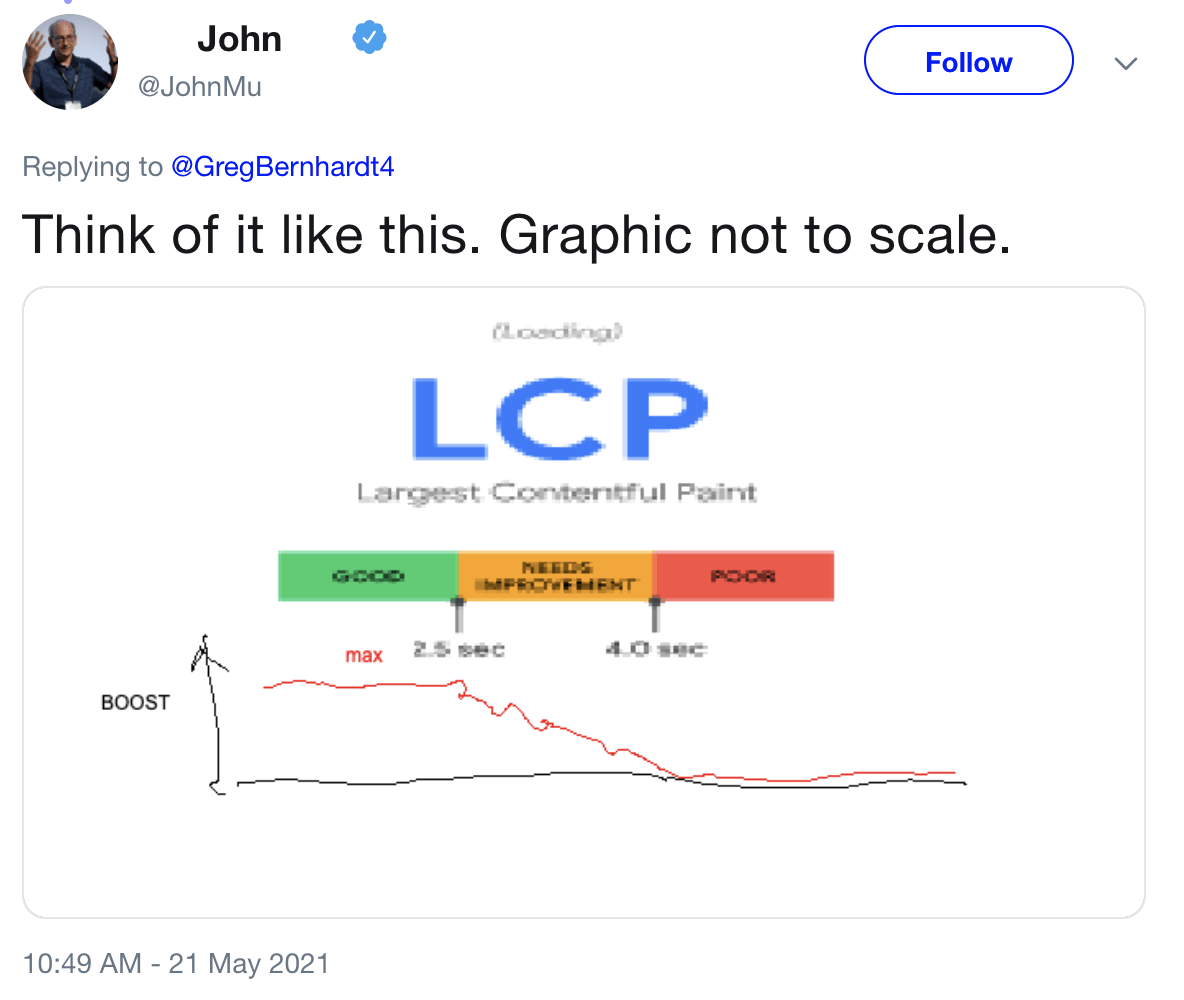

Moving from one category up to another is good for your users—pages load faster and more consistently—and may even offer a small boost to search rankings.

But while every improvement to your Core Web Vitals serves to make your website a little better, the difficulty and effort required to keep making improvements increases. At a certain point, there may be no additional benefit to search performance.

This is where over-optimization comes in: it might be that the time and effort required to reduce your LCP (one of the Core Web Vitals metrics) from 2.5 seconds to 2 seconds could be better spent elsewhere, on optimizations that would have a greater benefit to your overall search visibility.

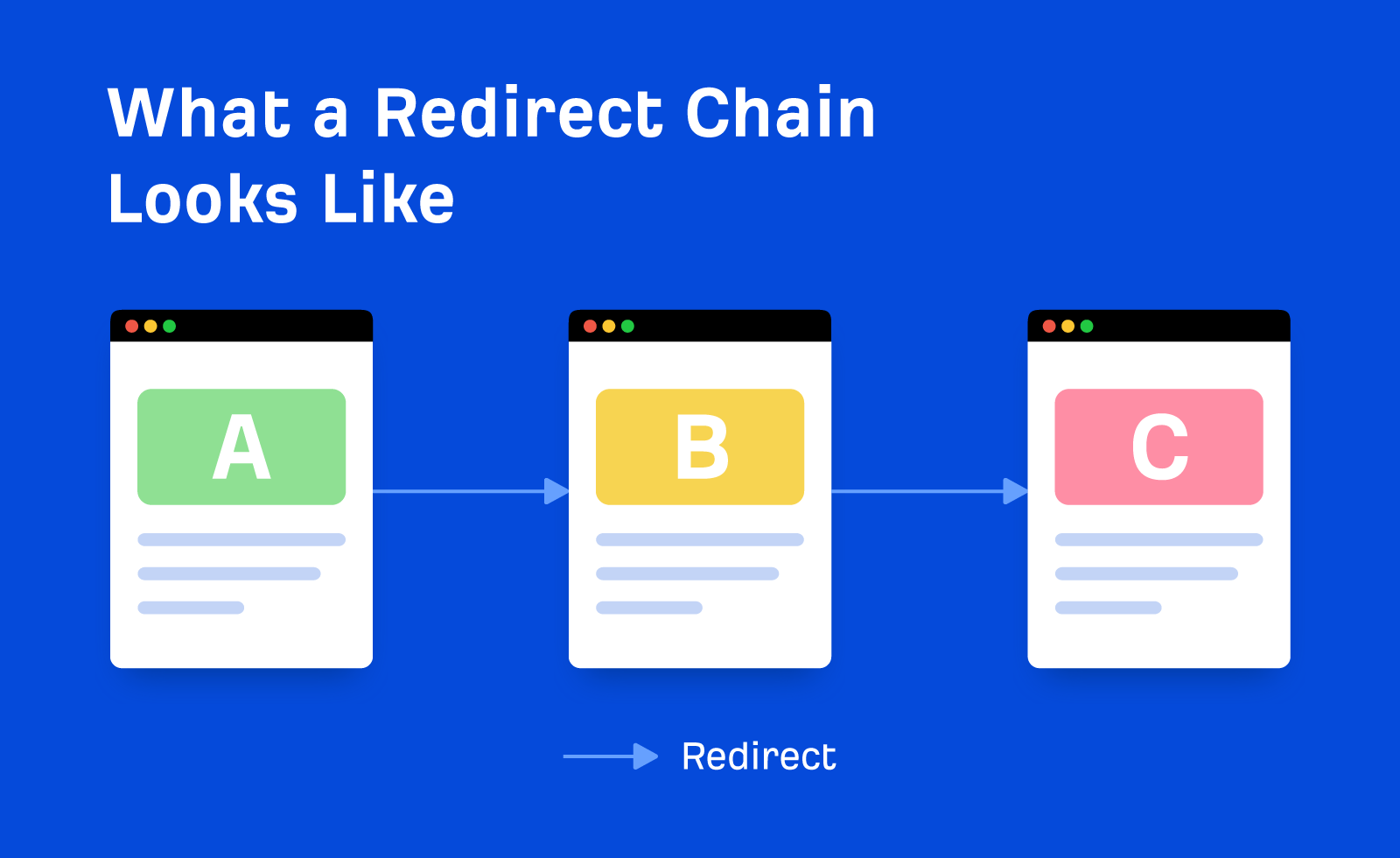

A redirect happens when a visitor to a web page gets sent to a different page—a redirect chain happens when several of these redirects happen in a row.

For example: a visitor to a now-deleted blog post might be redirected to a newer blog post; if that post is deleted, they might be redirected to the blog homepage.

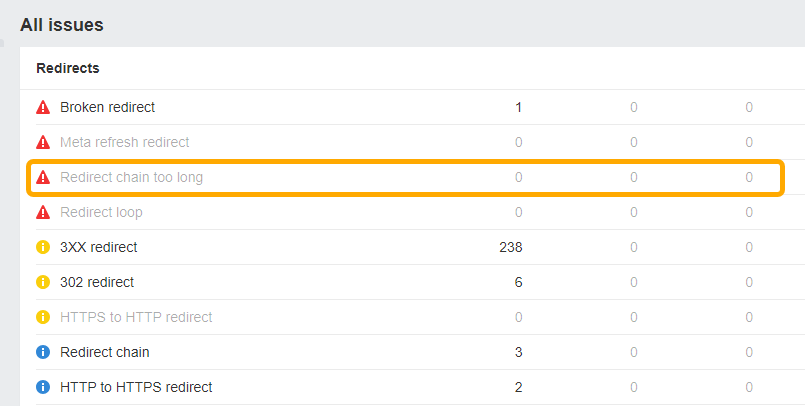

These redirect chains can get big quite easily, and it’s tempting to spend energy shortening them—but there’s probably little need. Google can technically follow up to 10 redirects before triggering an error, so most of your redirect chains are probably fine, as-is. If you want to play it safe, take John Mueller’s advice: fix redirect chains with five or more “hops.”

You can spot these using Site Audit. Head to the All Issues report after running a website crawl, and you’ll see a host of potential redirect issues, including “Redirect chain too long:”

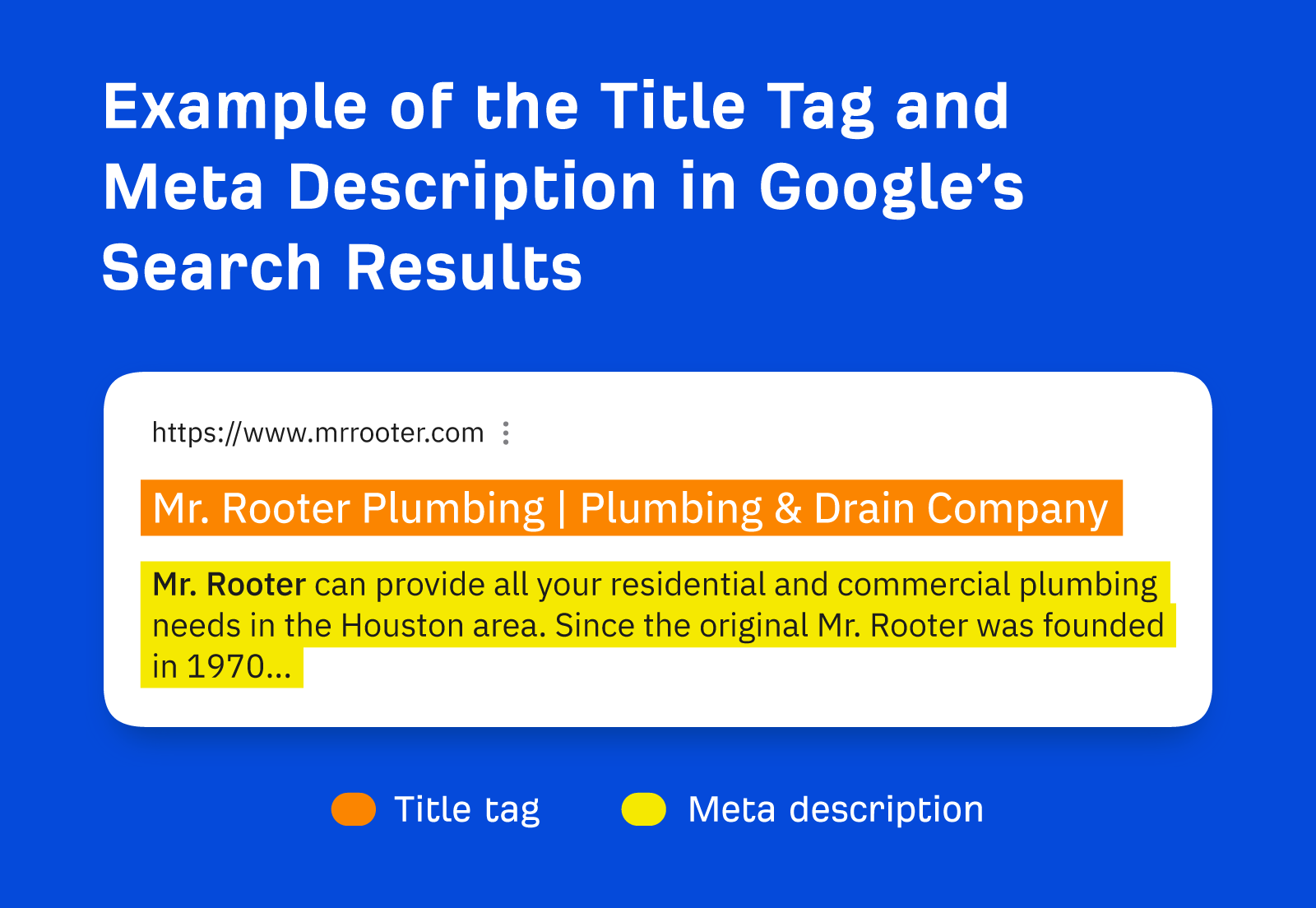

Meta descriptions and title tags help articles stand out in search results, and encourage searchers to click on your article.

With extra clicks on the line, it might be tempting to write or rewrite every meta description and title tag you can lay your hands upon—but that would entail a lot of wasted effort. Even on healthy websites, many pages receive little-to-no traffic from Google, so you’d change content that no one would see.

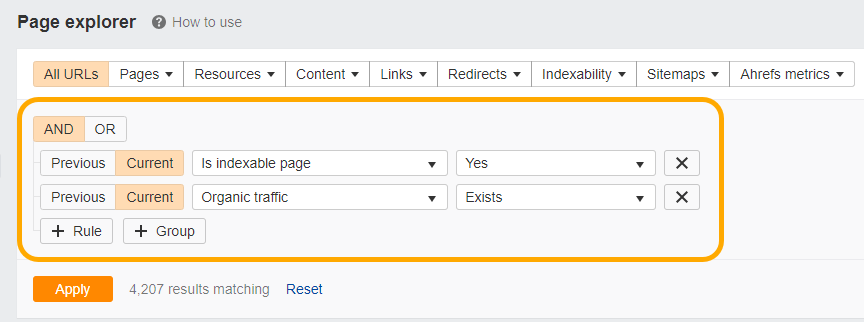

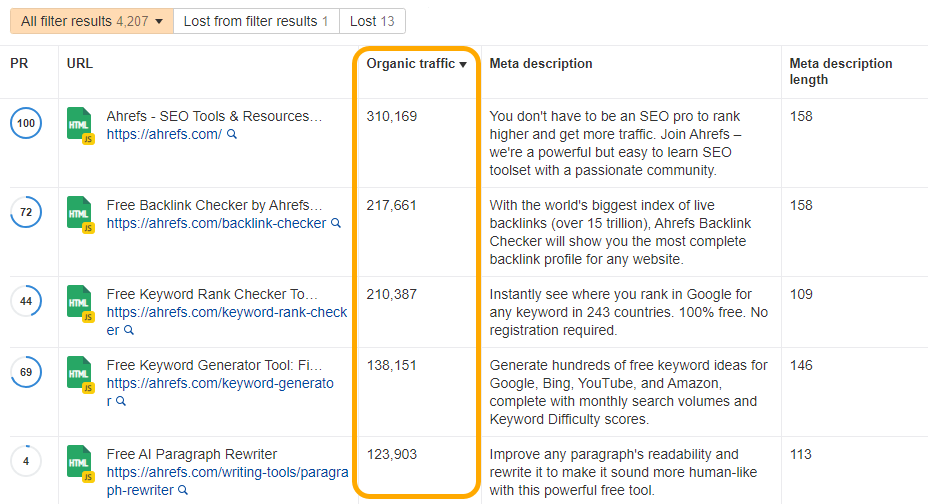

If you want to optimize meta descriptions and title tags, you need to prioritize. Site Audit works well: open the Page Explorer report and set the filters to show indexable pages that receive organic traffic:

Then sort your results from high to low by estimated organic traffic (you can even use the “Columns” menu to add columns showing each page’s current meta description and length).

You’ll see a list of your highest-traffic pages alongside their current meta descriptions, making it easy to see if any would benefit from an update.

Final thoughts

If you’re worried about over-optimization, your intuition is probably a good guide. If you feel like you’re doing something that Google (or your users) won’t like, or you’re fixating on tiny improvements in areas that already perform well—then yes, you’re probably over-optimizing.